Mesh Generation

Meshes are a way to model 3D shapes as a set of basic faces, delimited using edges and points. Usually, it is not the standard representation of shapes in 3D CAD softwares because it does not allow modeling exact geometries in the form of parametric curves and surfaces (such representations are called Boundary representation or B-rep). Nevertheless, their simplicity (only points, line segments and simple faces are used to represent a shape) has made meshes the representation of choice for many applications like rendering, slicing for 3D printing, etc. We purposely did not mention the use of meshes to perform FEM (Finite Element Method) analyses, as in this case, meshes are no longer used for their simplicity, but for their ability to carry and propagate information through bodies.

Most CAD parametric modeling software offer mesh generation and manipulation possibilities, and FreeCAD is no exception. FreeCAD hosts a workbench dedicated to working with meshes that offers many useful tools and functionalities, and we will focus on the one that allows generating meshes from FreeCAD shapes: Mesh FromPartShape.

The tool allows using four different meshing algorithms, namely: Standard, GMSH, NetGen and Mefisto. We will focus on the first one, as the three others are dedicated to FEM analysis meshes, and are not in-house.

The standard algorithm

The goal of this page is to provide an insight into how meshing works and can be set up from a high-level point of view, without entering into details into the complex operations occurring during the generation of meshes. The standard algorithm stands for the meshing algorithm provided by OCCT, FreeCAD’s geometric modeling kernel. This algorithm generates surface unstructured meshes and basically works in two steps:

- Edges of the shapes are first discretized, meaning that curves are transformed into polylines (thus closed contours become polygons),

- Then, surfaces are tessellated, meaning they are covered using geometric shapes, triangles in our case.

Generating a mesh from a shape is a complex operation, and implies hidden actions and parameters, which can lead to behaviors that are not trivial to understand, in particular regarding the setting of the 3 parameters we have access to. Let’s have a look at their influence with practical examples to better understand how to define good set-ups, and eventually generate good meshes.

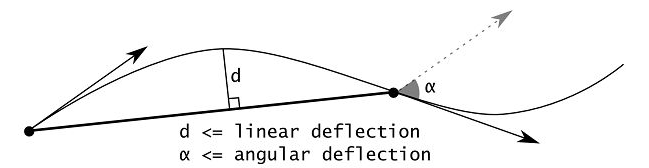

Angular deviation

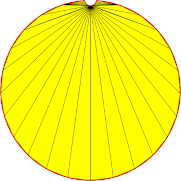

The angular deviation is mainly used at the edges discretization step. This parameter helps ensure the smoothness of polylines that represent curves by preventing sharp angles between consecutive line segments. Edge discretization has a great impact on the overall meshing of the shapes, because points (at the transition between line segments) generated at this step will serve as basis nodes for the construction of triangles that will further be used to tessellate faces delimited by the edges.

This parameter value is relative to the size of the shape to be meshed: regardless of the shape's size, a high angle value may lead to sharp transitions between consecutive line segments, whereas a low value will ensure smoother transitions.

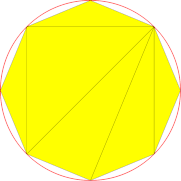

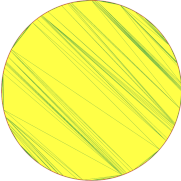

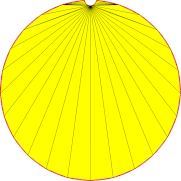

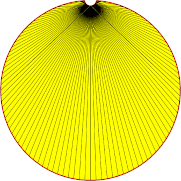

To illustrate the behavior of the standard algorithm regarding angular deviation, let’s vary this parameter while meshing a simple circular surface. As the surface deviation parameter also plays a role in the process, it has been set to a value high enough to avoid any interference with our demonstration: our circle diameter is 50mm, and so is the surface deviation.

Reducing angular deviation has a significant influence on the aspect of the mesh, limiting sharp angles when representing the face contour. If it allows increasing the fidelity of the mesh relative to the original shape, it does not provide an absolute value for the maximum deviation tolerated between the two.

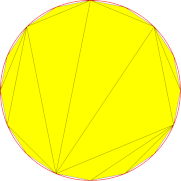

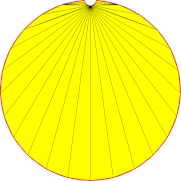

Surface deviation

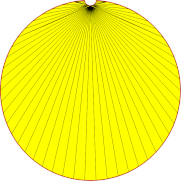

To do so, surface deviation is a better pick. It allows specifying the maximum deviation the mesh should be present compared to the original shape. Let’s get back to our circular surface to understand its influence.

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Surface deviation: 50mm Angular deviation: 90° |

Surface deviation: 10mm Angular deviation: 90° |

Surface deviation: 1mm Angular deviation: 90° |

Surface deviation: 0.1mm Angular deviation: 90° |

The influence of surface deviation is clearly visible and easily understandable in our example, given its absolute nature. It is particularly visible close to the edge: high values (50mm - 10mm) have no impact, whereas many triangles are added to ensure the 0,1mm tolerance.

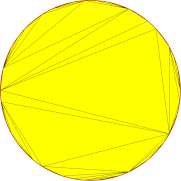

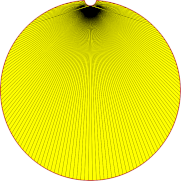

Combined influence of angular and surface deviation

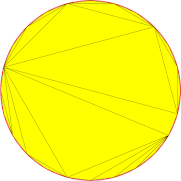

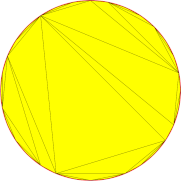

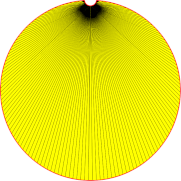

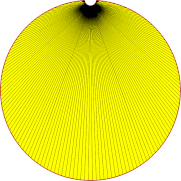

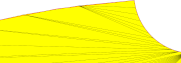

Decreasing either angular deviation or surface deviation has a similar impact on the mesh. This redundancy can lead to undesired behavior when bad parameter combinations are used: the following example shows the generation of unnecessary, oddly shaped triangles when both angular and surface deviation are set to low values.

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

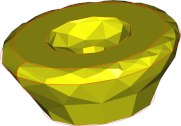

Surface deviation: 10mm Angular deviation: 30° |

Surface deviation: 3mm Angular deviation: 7° |

Surface deviation: 1mm Angular deviation: 5° |

Surface deviation: 0.1mm Angular deviation: 1° |

First synthesis

The above examples show that it is possible, using angular and surface deviation, to obtain meshes within the requested tolerance of the original shape and achieve the desired smoothness when representing curves. They also show the importance of an adequate setting and that simply setting low values may not yield the best meshes.

The devil is in the details

While our circular shape provided a good understanding of the influence of the parameters on mesh generation, it is unfortunately too simplistic compared to real-life meshing challenges. A common case is the presence of fine details on bigger shapes. Let’s add a detail to our circular shape: a smaller circular edge at the top.

|

|

|---|

|

Angular deviation / Surface deviation |

90° | 30° | 5° |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5mm |  |

|

|

| Nb of triangles | 10 | 32 | 149 |

| 1mm |  |

|

|

| Nb of triangles | 18 | 34 | 188 |

| 0.1mm |  |

|

|

| Nb of triangles | 53 | 59 | 207 |

|

Angular deviation / Surface deviation |

90° | 30° | 5° |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5mm |  |

|

|

| Nb of triangles | 10 | 32 | 149 |

| 1mm |  |

|

|

| Nb of triangles | 18 | 34 | 188 |

| 0.1mm |  |

|

|

| Nb of triangles | 53 | 59 | 207 |

Lowering angular deviation results in a rapid increase in fidelity between the mesh and the original shape. This is done at the expense of rapidly increasing the number of triangles. On the other hand, lowering the surface deviation allows generating meshes that just meet a requested tolerance, with as many triangles as needed, but the smoothness of the curve representation may be crude.

Again, one may note the redundancy between the respective influences of angular and surface deviation, and that some sort of convergence is achieved regarding mesh fidelity, even as more triangles are added, particularly when lowering angular deviation. This underlines once again that finding a good setting is better than simply choosing a low parameter value.

Hidden parameter example

High values of surface and angular deviations do not lead to the suppression of detail at the top of our shape during mesh modeling. This is an example of the effect of hidden operations and parameters within the meshing algorithms: particular types of edges, and circular edges, among others, have a lower limit of points for their polyline representation. In this case, the minimum of 4 points will result in at least three segments within the polyline. This can be highlighted by meshing a similar shape, but instead of a circular curve, a spline has been used to model the detail at the top. The minimal number of points then does not apply, and the detail is totally inhibited when high values of surface deviation are used.

| Geometrical nature of the detail | The shape | The mesh | A close view |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arc of circle |  |

|

|

| Spline curve |  |

|

|

Second synthesis

These examples, including details within larger shapes, which are very common in real life, show that adapting the discretization precision to the size of the entities to be meshed can lead to better trade-offs between mesh precision and complexity. Sometimes it can even be mandatory, for instance, when performing automated meshing operations, where a user cannot intervene to set up the surface deviation based on the shape size.

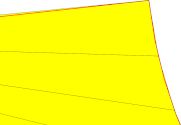

Relative surface deviation

A solution is to set the surface deviation as a function of the edge length, which is achieved using the relative surface deviation parameter. The principle is to scale the acceptable tolerance between the mesh and the original shape as a function of the shape's size. For instance, a value of 0.1 will lead to a surface deviation of 10cm on a 1m edge, and a 1m surface deviation on 10m edge. Let’s take a look on the results on our test shape.

|

|---|

|

Surface deviation (relative) & Angular deviation |

The mesh | A close view | A closer view |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 - 30° |  |

|

|

| 0.001 - 30° |  |

|

|

The evolution of the surface deviation parameter (which is now a relative parameter, so the ‘mm’ unit when setting it in FreeCAD may be confusing) applies the same way to the discretization of both the long and short edges. The side effect of using the relative surface deviation is that it does not guarantee an absolute maximum deviation between the mesh and the original shape.

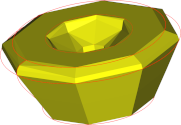

Surface tesselation

Our first thoughts focused on shapes and contours because they are the first entities to be discretized and have a significant influence on face meshing. Let’s dive a little bit more in surface tesselation using the standard algorithm. It applies Delaunay triangulation, using the Watson algorithm. Delaunay (from a Russian mathematician) triangulation is a way to generate points on a surface in a way that ensures triangles formed using the points will not intersect.

In addition, it optimizes triangle generation so that the angles are not too small, making them look well-shaped. That being said, as often, practical implementation to address real-world problems is complex and presents many challenges. OCCT meshing algorithms have been designed to mesh shapes generated with the BRep modeler, most often mechanical and engineering designs, which were the primary use cases the geometric modeler was initially developed for.

Thus, dedicated surface tesselation routines are used for the most common surface types in mechanical design, e.g., planar, cylindrical, conical, spherical, … to ensure performance and optimal tesselation. If the parameter settings affect all surface types, let’s examine their influence on B-spline surface tesselation to avoid biases introduced by predetermined tesselation strategies.

| [[File:3D_orig_vignette.png | none|alt=A BRep shape with BSpline surfaces|A BRep shape with BSpline surfaces]] |

|---|

|

Angular deviation / Surface deviation |

90° | 30° | 5° |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5mm |  |

|

|

| Nb of triangles | 196 | 666 | 9730 |

| 1mm |  |

|

|

| Nb of triangles | 376 | 790 | 26128 |

| 0.1mm |  |

|

|

| Nb of triangles | 3002 | 3262 | 36366 |

Conclusions are in line with what we saw with faces: angular deviation has a significant impact on the mesh aspect, while surface deviation guarantees a fidelity level at the lowest cost in terms of mesh complexity, but generates visible facets. Thus, a trade-off is to be found between the quality of the mesh regarding fidelity and smoothness, and the size of the mesh in terms of the number of triangles.

If you are curious about the impact of growing the number of triangles, you can have a feel by playing with the Minimum angular deflection parameter of your favorite software (Edit → Preferences → Part/Part Design → Shape view), which defines the fidelity of meshes used for visualization. A too-low value will lead to higher loading times and jerky manipulation of complex shapes.

Another way to perceive the impact of parameters is to transform our meshes into real objects by 3D printing. Resin printing (SLA) with a 0.05mm layer height will reveal some details.

|

Surface deviation & Angular deviation |

0.1mm - 90° | 5mm - 5° | 0.1mm - 5° |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface picture |  |

|

|

| Surface picture |  |

|

|

| Nb of triangles | 3002 | 9730 | 36366 |

These close-up pictures reveal that focusing only on surface deviation, even at low values, may lead to visible artifacts on the part's surface (as the zoom level is high, meshing impacts are not to be confused with printing layers, which are also visible as iso-lines on the pictures). It is difficult to differentiate the 9730-triangle mesh from the 36366-triangle one in terms of visual quality. Then, if it is the criteria, the lighter mesh (487ko vs 1.8Mo) should be preferred, as the other one provides assurance that the 0.1mm tolerance is respected everywhere in the part.

Last synthesis

As a synthesis, meshing algorithms are complex by nature, and angular deviation and surface deviation are working together in an intricate way that is not trivial to understand. One could be tempted to lower these parameters so the mesh fits seamlessly to the original BRep shape. This would lead to meshes made of many triangles, which will take time to be generated, to be processed in further applications, and will produce heavy files.

Parameters set-up workflows

From what we saw, a typical workflow to set the parameters is to first set surface deviation as a function of required fidelity between the mesh and the original shape, if any. Then, the angular deviation parameter can be used to adjust the smoothness of discretized surfaces to the required level, for visual or touch aspect, for instance. Another approach is to use a low enough angular deviation in order to achieve the desired smoothness, with no guarantee to fulfill an absolute geometric tolerance, and often at the cost of complex meshes. In those cases where no tolerance on fidelity is needed, another option is to use the relative surface deviation, which will adapt the size of the mesh elements to the original shape and the size of the details.

Setting your meshing set-up as FreeCAD default

As explained in the Preferences section of the function wiki, you can define your preferred surface deviation, angular deviation and relative surface deviation values as default, so you can mesh most of your shapes without even thinking about it!

|

|---|

Export your meshes

Once meshes have been generated with the adequate parameters, you can eventually export them with Mesh Export to a file in the format of your choice among the several options FreeCAD offers!

- Miscellaneous: Import Mesh, Export Mesh, Mesh From Shape, Regular solid, Unwrap Mesh, Unwrap Face

- Modifying: Harmonize Normals, Flip Normals, Fill Holes, Close Holes, Add Triangle, Remove Components, Remove Components Manually, Smooth, Refinement, Decimate, Scale

- Boolean: Union, Intersection, Difference

- Cutting: Cut, Trim, Trim With Plane, Section From Plane, Cross-Sections

- Components and segmentation: Merge, Split by Components, Segmentation, Segmentation From Best-Fit Surfaces

- Analyze: Evaluate and Repair, Face Info, Curvature Plot, Curvature Info, Evaluate Solid, Bounding Box Info

- Additional: Import Export Preferences, OpenSCAD Workbench, Mesh Scripting

- Getting started

- Installation: Download, Windows, Linux, Mac, Additional components, Docker, AppImage, Ubuntu Snap

- Basics: About FreeCAD, Interface, Mouse navigation, Selection methods, Object name, Preferences, Workbenches, Document structure, Properties, Help FreeCAD, Donate

- Help: Tutorials, Video tutorials

- Workbenches: Std Base, Assembly, BIM, CAM, Draft, FEM, Inspection, Material, Mesh, OpenSCAD, Part, PartDesign, Points, Reverse Engineering, Robot, Sketcher, Spreadsheet, Surface, TechDraw, Test Framework

- Hubs: User hub, Power users hub, Developer hub